In the early 2000s, the web didn’t just grow; it exploded. That revolution was powered by a shared mental model—the LAMP stack—which gave a generation of builders a standard blueprint for success. Today, we are facing a similar turning point with AI agents.

2000s-era LAMP referred to four of the key web app technologies—Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP—but it was more than an acronym: It established the standard architecture for dynamic web applications in summary form, enabling developers to rapidly create millions of web apps from a repeatable recipe.

Today’s agentic ecosystem is currently “exploding” with technologies – new AI protocols, frameworks, services, models, and tools appear daily – but has yet to explode with widespread business success. The reason? Rapid AI innovation has created a critical delivery challenge: a widespread knowledge gap. The ingredients needed to build secure and effective AI agents exist, but we lack a common architectural language to turn them into production business outcomes at scale. Extracting business value from agents is no longer an AI readiness problem, it’s a human readiness problem:

Getting hundreds of millions of trusted AI agents into production requires getting millions of developers fluent in agentic architecture.

Web-era technologies won’t help us, but we can run their playbook for building shared comprehension out of chaos. The new agentic LAMP stack provides a framework for understanding the core components of both augmentative and autonomous AI agents, offering a common vocabulary for developers, architects, vendors, and business leaders.

Defining the Agentic LAMP Stack: A Recipe for Agents

LAMP models the software architecture of a particular type of application: AI agents. It focuses on the core technologies an agent uses when performing its job (in technical terms, the agent’s runtime components) versus the technologies or tools used to develop the agent.

These components can determine an agent’s safety, quality, performance, and cost, making technology and vendor choices mission critical. Understanding the model enables technical and business decision makers to collaborate in ensuring that agentic projects get to production quickly and deliver expected outcomes while protecting both customer privacy and the security of the company’s data and systems.

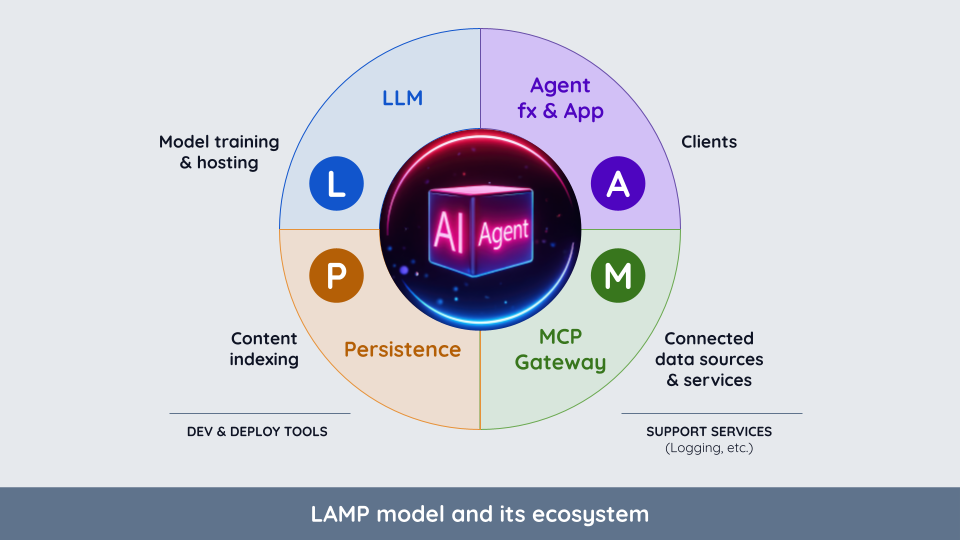

The LAMP stack consists of four key components, each with a distinct role in an agent’s operation (see Figure 1).

It’s tempting but misleading to use human cognition as a LAMP analogy. For instance, what humans would call “memory” isn’t just LAMP’s persistence component; it also includes the LLM’s trained knowledge, the framework’s context state, and the content of MCP-connected databases, filesystems, and business services. Smartphones offer a closer comparison: The phone’s various processor chips are the LLM (“L”) component; the phone’s device storage is Persistence (“P”); the touchscreen and system apps are similar to the “A” component, and the combination of the phone’s cellular and Wifi networks plus its USB socket collectively map to the MCP (“M”) component.

The following table provides a quick reference for each of the four components.

AI LAMP Stack Quick Reference

Component | Definition | Examples circa | |

L | LLM | The large language model and inference engine used for analysis, reasoning, and generation. | OpenAI’s GPT-5 pro, Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5, Amazon Bedrock Nova 2 Pro, Llama 4, DeepSeek-V3, etc. |

A | Agent Framework | The LLM orchestration, application-specific code, and “form factor” (chatbot, document processor, etc.) | LangChain, LangGraph, AWS Strands, CrewAI, Google ADK, n8n.io, Pydantic AI, OpenAI Agents SDK, etc. |

M | MCP Gateway | Connection and access control to both MCP services and conventional business systems and data | Vendia, TrueFoundry, MintMCP, Amazon Bedrock Gateway, FastMCP (os and commercial), IBM Context Forge, etc. |

P | Persistence | Semantic knowledge base(s) outside the LLM, such as vector-indexed documents. Uses: RAG, MCP queries, long-term agent memories | Pinecone, Mem0, Weaviate, AWS OpenSearch, Elasticsearch Relevance Engine, Milvus, pgvector (Postgres extension), Chroma, etc. |

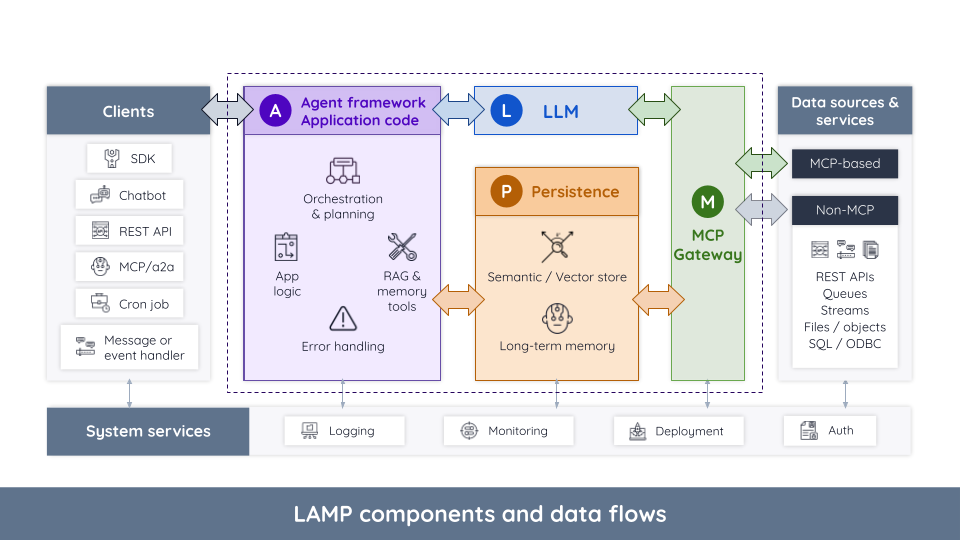

LAMP Stack Component Architecture and Dataflows

Each individual component of the agentic LAMP stack plays a strategic role when designing, building, and scaling robust AI systems. The sections below go into deeper detail on the capabilities, protocols, and dataflows of each of the four components as illustrated in Figure 2.

L: LLM

A Large Language Model (LLM) is typically the foundational reasoning engine in an agent, handling natural language comprehension, intent detection, analysis and research, and content generation.

Component properties common across vendor enterprise SKUs:

- A proprietary, reactive, mostly synchronous REST API to perform inference

- Support for data sovereignty and control

- Built-in MCP protocol support for tool selection and usage plus a basic MCP client UI (“clickops”-based; programmatic support is nascent)

Component form factors:

- LLM-aaS: Integrated model and hosting from a single provider

- Easy to use REST APIs such as Claude’s /messages, OpenAI’s /responses

- Model hosting-aaS: Serverless inference for BYO models

- Model flexibility: stock catalog, BYO, custom, tuned variants, etc.

- Deployment flexibility: geo, GPU type, instance type, VPC config

- Example: Amazon Bedrock for non-Nova models

- Inference API(s) vary by model

- Embedded / Self hosted

- Highest degree of control and complexity; may be lower cost

- Required for scenarios such as air gapped deployments

- Open source/open weight and commercial third party offerings, packaged as weight data, library, or Docker container

- Can also be custom or tuned first party models/variants

- Inference API(s) vary by model

Trends affecting this component:

- Better models, less customization: As models improve, context windows grow larger, and MCP exposes vector stores directly to the LLM, the need for every company to “teach” LLMs about their industry, terminology, policies, etc. is fading. While boundary-pushing use cases like drug research and hedge funds will continue to require custom models, most businesses will start treating LLMs like browsers and operating systems.

- Complexity “shifts right”: Agent frameworks and design patterns like RAG were invented to deal with gaps in early LLMs that couldn’t handle multi-step activities well, reflect on their progress and proposed answers, or effectively generate search queries. Modern LLMs are increasingly removing the need for “boilerplate” frameworks, resulting in “prompt stuffing” techniques like RAG (typically drawn on the left side of the LLM) being replaced with LLMs organizing their own semantic searches through MCP (typically drawn on the right side of the LLM). Net result: Agent frameworks are getting slimmer, while MCP Gateway governability and observability is becoming more vital.

- MCP convergence, inference divergence: MCP is already a de facto standard and continues to improve. However the LLM’s own APIs are diverging on key aspects, such as whether the LLM (OpenAI) or the agent framework (Anthropic) should manage context. Net result: LLM substitution is getting harder; adopters will need to commit to a vendor or be prepared to invest in a portability layer and testing overhead.

Key business impacts for this component:

- Privacy and control versus flexibility and speed – The embedded-vs-hosted LLM decision mirrors existing on-prem vs public cloud and build-vs-SaaS tradeoffs but with a 10X innovation/replacement pacing.

- Replacement cost model and unit of scaling – To accurately predict and measure ROI and COGS, compare costs and LLM pricing models based on what the agent replaces: Customer- or employee-facing features and customer support staffing versus “headless” agents handling on-demand or batch workloads.

- Price/power spectrum – LLMs are converging on a hardware-like pricing model, with low cost LLMs offering “good enough” capabilities to high-end models offering extensive reasoning, on-demand web research, and multi-modal comprehension. Ensure financial owners have visibility into model selection cost implications.

Key decisions for this component:

- Does your use case demand a self-hosted model? If not, serverless hosting solutions are much easier to implement and support.

- Do your requirements demand a fully or partially customized model? Using stock models eliminates a huge swath of training and testing complexity, cost, and risk.

- Vendor-specific needs / willingness to be “locked in” to proprietary features? Diverging application models among the major vendors and between embedded and hosted approaches impact downstream LLM switching costs.

- Code versus prompt? Use code in the agent framework (‘A’ component) or MCP-connected sources when guarantees around data handling, cost, or deterministic processing are critical. For everything else: minimize the size, complexity, and cost of application code by shifting as much responsibility as possible to the agent’s LLM.

- Need for production-grade operations? LLM operational controls are still emerging; adopters can reduce “clickops in production” by selecting a vendor that offers programmatic MCP setup combined with an enterprise-grade MCP Gateway.

Component communication patterns:

- The LLM is only invoked from the agent framework, so that it can manage context, supply the correct prompt instruction and additional content (RAG, e.g.) and provide uniform processing of results. (Exception: Limited sub-query support built into MCP.)

- The LLM uses MCP to access additional data or services it requires. (Note that some LLM vendors and models break this rule with “direct” access mechanisms that bypass MCP governance and observability firewalls.)

- Typically the LLM does not communicate directly with the Agent framework/application component or the Persistence component (though it may optionally search the Persistence component’s data store via MCP).

A: Agent Framework and Application Code

The “A” component turns an LLM’s “think” API into a useful outcome. It conceptually includes two things (thankfully they both start with an “A”): Application Logic gives the agent its domain-specific purpose and determines its form factor, such as a chatbot, a REST API, or an event handler.

The Agent Framework defines the control flow around the LLM, acting as a sophisticated state machine that orchestrates the agent’s lifecycle, guides direction and tool usage, and handles error management. It governs not just what the LLM thinks about, but also how and how much—whether it should act linearly, reflect on its actions, or swarm a problem with multiple sub-agents. Since the code for both is typically intertwined, they’re presented as a single component.

Component properties common across vendor enterprise SKUs:

- Form factor and environment handling: Providing the agent’s external form factor (e.g., a web interface) and connecting it to its operating environment, including handling user authentication and authorization. Converting client requests to prompt parameters and query responses into client-specific formats.

- Prompt construction: Retrieving all the information needed for the prompt, including performing “fuzzy” semantic lookups via RAG patterns, structured data such as per-user settings, and templated directions specific to the agent’s domain and task.

- “Short-term memory”: Establishing and maintaining the agent’s workflow context between LLM calls (especially for fully stateless LLMs).

- “Outside-in” LLM coordination: Handling patterns that require LLM selection or coordination, such as

- Multi-step workflows and loops (plan, research, evaluate, refine/repeat)

- Using the same or different LLMs to handle segregated or firewalled activities from the primary LLM, such as query or response guardrails or compliance scanning

- Dynamic LLM selection – dispatching queries to different LLMs to optimize cost or quality on a per-query basis

- Implementing parallel LLM patterns (“swarming”, sub agents, multi-agent collaboration)

Component form factors:

The application code for agents is equivalent to conventional applications, but the agent framework portion of the ‘A’ layer will take on one of several distinct forms:

- Open source cloud- and AI-agnostic agent orchestration libraries

- Frameworks implemented as open source libraries (typically Python and Javascript/Typescript) that handle common agent orchestration needs

- The open source LangGraph framework is the the market leader in this form factor and overall

- Best for complex workflows that require a mixture of deterministic (conventional code and business processes) and non-deterministic thinking (LLM-based steps).

- Vertically integrated agent frameworks

Agent frameworks that trade agnosticism for out-of-the-box platform integration and simplicity:

- Public cloud. Example: Amazon Bedrock AgentCore + Strands. Simplifies integration with existing cloud-based services and data, such as turning an AWS Lambda function into an MCP tool or indexing documents stored in an S3 bucket.

- LLM provider. Example: OpenAI’s Agents SDK. Enables the provider to offer “agent as a service” instead of just the raw, low-level model capabilities. Potentially enables better quality and performance by integrating short-term and long-term memory than other approaches (though this has not yet been proven).

- Data lake and middleware providers. Platforms that handle customer data, such as Snowflake, or application middleware, such as Jitterbit, are integrating both agent framework and MCP support to “AI enable” their existing capabilities and simplify the process of creating agents on their platforms.

- Nothing (aka “prompt only”). For single task agents without complex orchestration requirements it may be possible to skip the agent framework entirely in favor of just a good prompt prologue in the application code.

- DIY (pure application code). At the other end of the spectrum, extremely complex, performance intensive, or high security agents may require entirely custom coding.

Trends affecting this component:

- Vertical integration on the high end. The “battle for who owns the context” has not yet been decided, but vertical integration has strong motivations that mean it’s here to stay. Both public cloud providers and OpenAI are vying to own more control over the agent framework and how it’s modeled.

- LLMs cannibalizing the low end. As LLMs get better at self-directed planning, result quality testing, guardrail enforcement, MCP tool selection and use, and query/code generation, they are eliminating the gaps agent frameworks were invented to address. Simple “black box” frameworks and RAG patterns are especially vulnerable to this trend.

- Frameworks are tackling bigger challenges. Instead of focusing on closing gaps in early LLMs, agent frameworks are refocusing to help solve more complex problems, such as multi-agent collaboration. Expect both use case/workload and industry/domain specialization to continue.

Key business impacts for this component:

- Lock-in. Adopting a cloud- or LLM-integrated framework means less code and faster time to market for agents but increases switching costs and lock-in risk.

- Cost. Agent frameworks per se have zero marginal cost today, but because they “drive” the LLM, they can have an outsized impact on cost, for example by calling the LLM more times than necessary or asking it to do unnecessary work.

Key decisions for this component:

- Platform specific or agnostic. Is vendor/platform lockin worth the advantages? Companies committed to a specific cloud provider (or to OpenAI) will benefit from adopting the “native” solution.

- Agent complexity. Can this agent be built with nothing more than a prompt injector or must it support complex swarming, long-lived “human-in-the-loop” business processes? Multi-agent collaboration, dynamic LLM selection, and long-lived, stateful business processes all indicate the need for a full-fledged agent framework.

Component communication patterns:

- The ‘A’ component is typically the only component allowed to call the LLM directly.

- The ‘A’ component is typically the primary caller of the Persistence (‘P’) component, using it to provide “semantically relevant” results to the LLM in RAG and similar patterns, as well as supplying long-term memories (if used).

- The ‘A’ component may use MCP (the ‘M’ component) to ensure that all access to backend systems and data flows through a common governance and observability channel. (But note that this design pattern is not yet firmly established.)

M: MCP Gateway

The ‘M’ component’s primary role is to abstract the complexity of integrating LLMs with the backend business systems that hold the data an agent needs to complete its tasks.

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) represents a critical standardization in how agents interact with external data and systems. This is a significant shift, replacing ad-hoc API wrappers with a universal connection layer. MCP is “HTTP for agents”, adding crucial capabilities like tool discovery, built-in OAuth and session support, and refining support for concepts like notifications and content management. Unlike the ‘L’ and ‘A’ components, the MCP protocol is a well-adopted de jure standard, at least for its core functionality.

Component properties common across vendor enterprise SKUs:

- MCP Protocol: Virtually every company and organization in the AI ecosystem has stated their support for the MCP protocol, making it a safe standard to adopt.

- Most modern LLMs have built-in MCP clients and are trained to use common tools, query languages, and data formats.

- Some hosted LLMs, such as OpenAI and Anthropic’s Claude, offer limited built-in MCP administration, usually via a “clickops” admin UI screen where MCP servers can be added or removed. Programmatic control over this feature is still largely missing or in “beta” at this time.

- MCP providers largely support core MCP features around tool discovery and use, sessions and streaming, and OAuth-based authentication. Beyond the basic features support and conformance taper off.

Component form factors

Note that the discussion below ignores “local” MCP servers, which are more prevalent in development than production.

- Manual configuration of the LLM’s built-in client to one or more remote MCP servers. This is the easiest approach for a small number of development and non-production agents that do not have requirements around uptime, scalability, deployment automation, etc. Only supports MCP-compatible targets. Does not offer advanced features such as namespace conflict resolution.

- Self hosted MCP-only Gateways (aka “MCP Routers”). Open source libraries such as FastMCP can be used as “MCP routers” that connect to multiple backend MCP servers. This enables solving challenges like namespace conflict resolution, but increases deployment and management complexity.

- Managed (“Serverless”) MCP Gateways (aka “MCP Routers”). Commercial offerings that offer MCP Gateway-as-a-Service, typically in conjunction with more powerful governance and observability tools.

- “Omni” Gateways. Managed MCP Gateways act both as MCP routers and handle non-MCP sources without requiring them to be wrapped, typically by adding API Gateway features to call conventional REST APIs as well as other protocols (JDBC/ODBC, sFTP, etc.) Examples: Amazon Bedrock AgentCore Gateway, Vendia’s Managed MCP Gateway and Data Integration Platform.

Managed gateways (both MCP-only and “Omni” varieties) can be used across a company’s agents, making them ideal to also provide a consistent solution to access controls, security, traffic management, catalog services, logging and monitoring, and other “ilities”.

Trends affecting this component:

- Customers outgrowing built-in clients. Manual configuration of “hard-wired” MCP at scale is no more tractable than it was for APIs. MCP Gateways will play the same architectural role that API Gateways play in enterprise stacks today.

- Omni for the win. Wrapping every existing API, service, file system, etc. is a daunting task for any size company. Omni gateways allow customers to gain value from their existing assets without additional migration projects or staffing requirements.

- Public clouds and data lakes have the upper hand on vertical integration. Platforms like AWS’s AgentCore are ideally positioned to not just offer a hosted Omni Gateway but can also streamline its integration with their entire cloud platform, enabling customers to use existing identity, deployment, storage, and compute solutions with minimal cost and risk. Data lakes have a smaller, but similar, “home field advantage” for data assets.

Key business impacts for this component:

- Use MCP to address data and system exposure risks. MCP Gateway is an apt metaphor – exposing sensitive data, such as customer PII, to a nondeterministic LLM carries risks. By virtue of being “upstream” of enterprise systems, the MCP component is an ideal place to focus data security, compliance, and governance.

- Avoiding spaghetti systems. Hard-wiring individual LLMs to multiple MCP servers that then connect to multiple backend systems, often mission critical ones, is an IT and SecOps nightmare waiting to happen. Consider the need for fleet-wide governance, monitoring, and migration management up front.

Key decisions for this component:

- Does your agent require enterprise-grade security, compliance, scalability, uptime, etc.? If so, the limited built-in client is likely to prove insufficient.

- Do you want to access non-MCP targets without first converting them? If so, an Omni Gateway is a necessity.

- Vertically integrated solutions from cloud and data lake providers offer the expected simplicity (and reuse) pros and lock-in cons.

Component communication patterns:

- ‘L’ (LLMs) calling MCP is the typical pattern.

- The ‘A’ component may also call MCP to centralize access to backend systems.

- MCP may call the ‘P’ (Persistence) layer, enabling the LLM to perform “RAG-like” semantic searches.

- The MCP protocol allows for controlled “traffic inversion” where the server can initiate requests back to the client, enabling ‘M’-to-’L’ communication. It supports asynchronous change notifications (e.g., an MCP tool’s parameters have been changed due to a new release) and features like “sampling”, where the client LLM is used as an LLM “subroutine” by the MCP server to help perform a task without requiring it to embed an entirely separate LLM.

P: Persistence

Persistence represents long-term “state” used by an agent. While a human concept like “memory” spans elements of all four LAMP components, the Persistence component plays the specific role of providing semantic searches, for example searching the text content of a collection of documents. It is commonly used to implement RAG architectures, where relevant contents are retrieved from a vector (or vector-keyword hybrid) index and used to supply relevant content to an LLM. Long-term “semantic memories” that span individual sessions can also be stored in the Persistence layer.

Semantic information has typically been retrieved by the agent framework and provided to the LLM as part of the prompt text. But as LLMs grow more capable, semantic queries are experiencing a “right shift”, with techniques like RAG being replaced or augmented by LLMs performing their own semantic searches via MCP.

However, even when accessed via MCP, the Persistence component is more than “just another data source” because it acts as a fundamental agent building block, with the choice of vendor and technology directly impacting an agent’s ability to recall and use salient information. By contrast, other MCP-connected data sources, like a company’s ERP system, are external to the agent and essentially fixed, as they must be shared with the company’s existing applications and processes.

Component properties common across vendor enterprise SKUs:

- Ingestion, storage, and retrieval (search) of vector-indexed content (at least textual, may support other or multiple modalities, such as images)

Component form factors:

- Dedicated vector databases and storage layers

- Built-for-purpose vector databases such as Pinecone, Milvus, and Weaviate captured the early RAG market and support specialized use cases such as low latency retrieval. AWS Vector Buckets target low cost, high scale vector storage for “cooler” data.

- Leading-edge GraphRAG solutions, such as neo4j and Microsoft’s GraphRAG that go beyond semantic searches to incorporate knowledge about relationships between objects.

- Commodity databases and datalakes

- Broad vector support by data lake vendors and popular extensions to operational databases, such as Postgres’s pgvector, have made the expense and complexity of a dedicated vector database unnecessary for many organizations. These solutions also offer seamless integration of structured and semantic searches and leverage existing SQL-based solutions.

- Content stores with built-in “hands-free” semantic search features

- Google’s Gemini and Microsoft’s Copilot provide built-in integration to their respective front office storage systems (Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive), including API and scripting support.

- Dedicated content stores such as Dropbox that offer integrated semantic indexing (Dropbox Dash).

- Business-targeted AI suites such as Amazon QuickSuite combine document storage, indexing, and search operations.

- Enterprise search products

- Search and operational analytics products such as Elastic’s Elasticsearch Relevance Engine and Amazon OpenSearch that combine keyword and semantic searching with powerful ranking algorithms.

Trends affecting this component:

- Commoditization: Specialized solutions like vector databases are losing ground to the “good enough” solution of vector features in conventional databases. Semantic search is now a built-in feature for most user-centric content stores. The dedicated market is now specializing into niche uses, such as embedded, and “frontier” technologies, such as GraphRAG. Former keyword search solutions like Elasticsearch are now “semantic by default”.

- “Right shift”: LLM intelligence is converting RAG to MCP: As LLMs start performing more of their own searches, the need for dedicated RAG solutions is giving way to better general purpose support that also supports LLM-initiated queries, such as Postgres pgvector.

- Beyond Vector: GraphRAG and other advancements: Existing semantic search approaches often fail at “multi-hop” questions that require understanding and traversing relationships. Researchers and commercial vendors such as neo4j are actively developing technologies that go beyond vector and keyword indexing, such as GraphRAG solutions that attempt to encode and search relationships and not just terms. Expect these and other advanced semantic search technologies to enter mainstream solutions over the next few years.

Key business impacts for this component:

- Control versus simplicity. “Easy button” solutions that leverage existing database, data lake, front office, or content management vendors avoid the complexity and cost of adding and integrating additional vendors and services and suffice for many use cases. Use cases that need fine-grained control over document indexing, multi-modal content, or highly optimized retrieval likely require a built-for-purpose product.

- Cost drivers. ‘P’ component costs are primarily driven by three factors: scale (the amount of information being indexed, such as the number and length of documents), freshness (how frequently the material needs to be rescanned), and query throughput (the rate at which queries are performed). Organizations with critical needs in two or more of these dimensions should perform detailed up-front cost modeling when comparing approaches.

- Security, compliance, and privacy concerns. As with the ‘M’ component, the Persistence layer of LAMP is a critical locus of information access control, as it can end up storing PII, company confidential, and other sensitive information.

- “Semantic Silos” and multi-vendor challenges. The growing ubiquity of semantic search capabilities also means nearly every company will find themselves with multiple semantic store technologies and vendors: public cloud services, operational databases, data lakes, content management systems, etc. Managing overlapping content and controls in this diverse environment may present significant challenges.

Key decisions for this component:

- Simplicity versus flexibility. Leveraging built-in features or extensions of existing solutions can minimize cost and complexity but also limits flexibility and control. Piloting with sample data and queries can help determine how effective built-in and off-the-shelf solutions are at addressing an organization’s needs and whether/where custom indexing or advanced capabilities are required.

- Number of solutions required. While a single MCP gateway solution can be adopted across an organization, the varying needs of the ‘P’ layer may require multiple solutions: vendor-integrated front office platforms, data lake-provided options for analytical information, text-optimized content store mechanisms for slow-changing data such as manuals, and combined keyword/semantic search technologies for scanning logs in real time.

Component communication patterns:

- The Persistence layer (‘P’ component) is most commonly accessed today by the agent framework to implement RAG. Some agent frameworks, such as AWS’s AgentCore, also use this pattern to implement long-term memories.

- LLM-initiated searches via MCP (‘M’ component) are a growing use case.

- The ‘P’ component is typically passive, and does not call into any other layer of the LAMP stack directly.

Outside the model

LAMP focuses on the runtime aspects of agents, which usually play the largest part in determining its safety, scalability, performance, quality of service, and cost. Other categories, though essential to the broader agent ecosystem, typically reside outside the model:

- Development-time tools and activities

- SDLC tools and services: IDE, code repo, test harnesses, deployment tools, etc.

- Models: batch training, tuning, and testing/evaluation jobs

- Batch jobs to ingest, update, or re-index the Persistence layer

- Exception: agents using these tools themselves via MCP, such as a virtual software developer using SDLC tools

- Enterprise data and services used as MCP tools or data

- REST APIs, internal apps, SaaS services, content stores, databases and datalakes, etc.)

- Exception: Persistence component content and tools accessed via MCP

- “Clients”, including anything that fires off an agent but isn’t part of the agent’s code

- SDKs, event handlers, REST API wrappers, chatbots, cron jobs, etc.

- Exception: The calling agent in agent-to-agent dispatch patterns

- Shared system services

- Logging, monitoring, identity, credential storage, etc.

- Exceptions: agents accessing these services themselves via MCP, such as a continuous auditing agent

LAMP in Action: Driving Agent Design Decisions

To see how the model can be used, consider a health insurance company designing an AI agent to help automate client billing services. The LAMP architecture helps to organize critical technology decisions and business tradeoffs:

- LLM: Current “off-the-rack” LLMs already understand a wealth of medical and insurance terminology, so fine tuning or custom models may not be needed, reducing cost and risk. However, prompts will likely need to be tuned and tested to ensure conformance to legal, regulatory, and policy guidelines. Query throughput and model complexity can form the basis of an initial agent cost model.

- Agent framework: This agent may need to be called from multiple clients, such as batch processing monthly billing cycles while also responding to customer or physician correspondence. It may be necessary to load company- or customer-specific policies along with applicable laws and regulations to ensure accurate processing and decisioning, so these would need to become part of the P layer and context management. Whether guardrails should exist as prompt guidance or separately is another key consideration for this layer.

- MCP Gateway: Real-time, structured business data such as customer preferences, billing history, current policy, etc. needs to be retrieved and updated in its existing systems of record, so this layer helps scope backend data and API requirements. Actions, such as sending texts or emails to customers, need to appear as MCP tools in order for the LLM to use them. The MCP Gateway also handles access controls and monitors data and service usage by the agent, making it a natural component to scope PII and PHI exposure and compliance.

- Persistence: Policy and regulatory specifics not encoded in a general purpose LLM will need to be itemized for storage here. Implementors will also need to decide if the agent will be permitted to develop and retain a “semantic profile” of customers, such as their sentiment, preference for level of detail in explanations, and so forth. Profiles for physician offices could be included to facilitate error pattern detection, such as a history of mis-coding a particular type of treatment. Security and compliance reviews can focus here and on the ‘M’ component.

LAMP’s Strategic Value: From architectural clarity to business advantage

The value of the agentic LAMP stack extends well beyond a technical diagram. It provides a strategic framework for making critical development and business decisions, enabling teams to build more robust, scalable, and maintainable AI systems.

Optimizing Design Patterns

The LAMP architecture can help teams think through design approaches and tradeoffs in advance, as well as avoid common pitfalls, such as:

- Decoupling Logic from Tools (A vs M). By recognizing MCP as a distinct data and service gateway, teams can avoid bloating the Agent Framework (‘A’ layer) with bespoke API integrations. This architectural separation allows the framework to focus purely on reasoning patterns and orchestration logic, while the MCP Gateway abstracts the messy reality of connecting to diverse enterprise systems like ERPs and CRMs. This decoupling leads to cleaner, more modular code that is easier to manage and scale.

- Defining State (P vs M). The framework resolves the common confusion over where data should reside. It provides a clear rule: if the data is an external record of truth that the agent queries (like a customer’s current account balance), it is accessed via the MCP layer (‘M’). If the data is part of the agent’s internal knowledge base or memory (like a policy document used for RAG or a memory of a past conversation), it lives in the Persistence layer (‘P’). This distinction clarifies data ownership and “left side versus right side” access patterns.

Streamlining Business Decisions

A common nomenclature helps organize the rapidly emerging vendor ecosystem and streamline cross-functional decisions. The “build versus buy” analysis becomes simpler when technologies can be mapped to a specific layer. Organizations can select best-of-breed ‘L’ providers for models, adopt open-source ‘A’ frameworks for orchestration, procure ‘M’ platforms for enterprise connectivity, and choose specialized ‘P’ vendors for semantic storage and search. Security, compliance, and executive teams can more easily assess and review agent-related risks through an understanding of how these considerations play out in (and across) each of the LAMP components.

This clarity not only accelerates development but also aligns technical, operational, security, and business teams around a shared understanding of the architecture, particularly for enterprise-critical components like the MCP layer.

Conclusion: A Shared Map for the Agentic Frontier

Like the original LAMP stack, this new model is a simplification of a complex and evolving technology landscape. Real-world architectures are messy; an LLM vendor might choose to add non-MCP tools directly to an LLM or an agent framework be entwined with a specific persistence layer.

The value of a model lies not in its absolute perfection but in its ability to offer a shared language for design, discussion, and decision-making in a field that is still defining itself. Successful business adoption of agents requires not just game-changing AI technology but also the clarity that emerges from a shared understanding among the humans putting it into production.