Think of the design of a simple item — a chair.

A chair has a simple function understood the world over, and it can be described somewhat universally. But what would a chair look like that was built without any glue or nails? With only a lathe and a drill press? With only access to 1×1 inch stock? Because of limits created by tools, experience, and shipping, there are huge gaps between a piece of furniture made by a carpenter in the 1800s and now.

In IT, we encounter these same sorts of limits all the time, and some of the best-paid engineers are the ones who can best work with those limits and reshape original ideas into problems that can be solved by computers. Take Alexa — it is supposed to solve the problem “humans want to ask something in their home questions and get answers.” It instead is built to route human-supplied questions between a huge number of different question-specific applications (Alexa Skills) running in the cloud, far away from the device in a person’s home. The constraints of the technical tools change the non-code components of your system.

Real-time, multi-party data sharing product evolution

Let’s take for example a common business need that ends up requiring different technical gymnastics depending on the technology in use; a payment or invoicing system.

Invoicing systems need to support multiple parties sending and receiving invoices for an ever-increasing number of products. The fastest-to-market version of this system would involve no code at all: literally allow parties to physically mail invoices and paper checks, then open and process them manually.

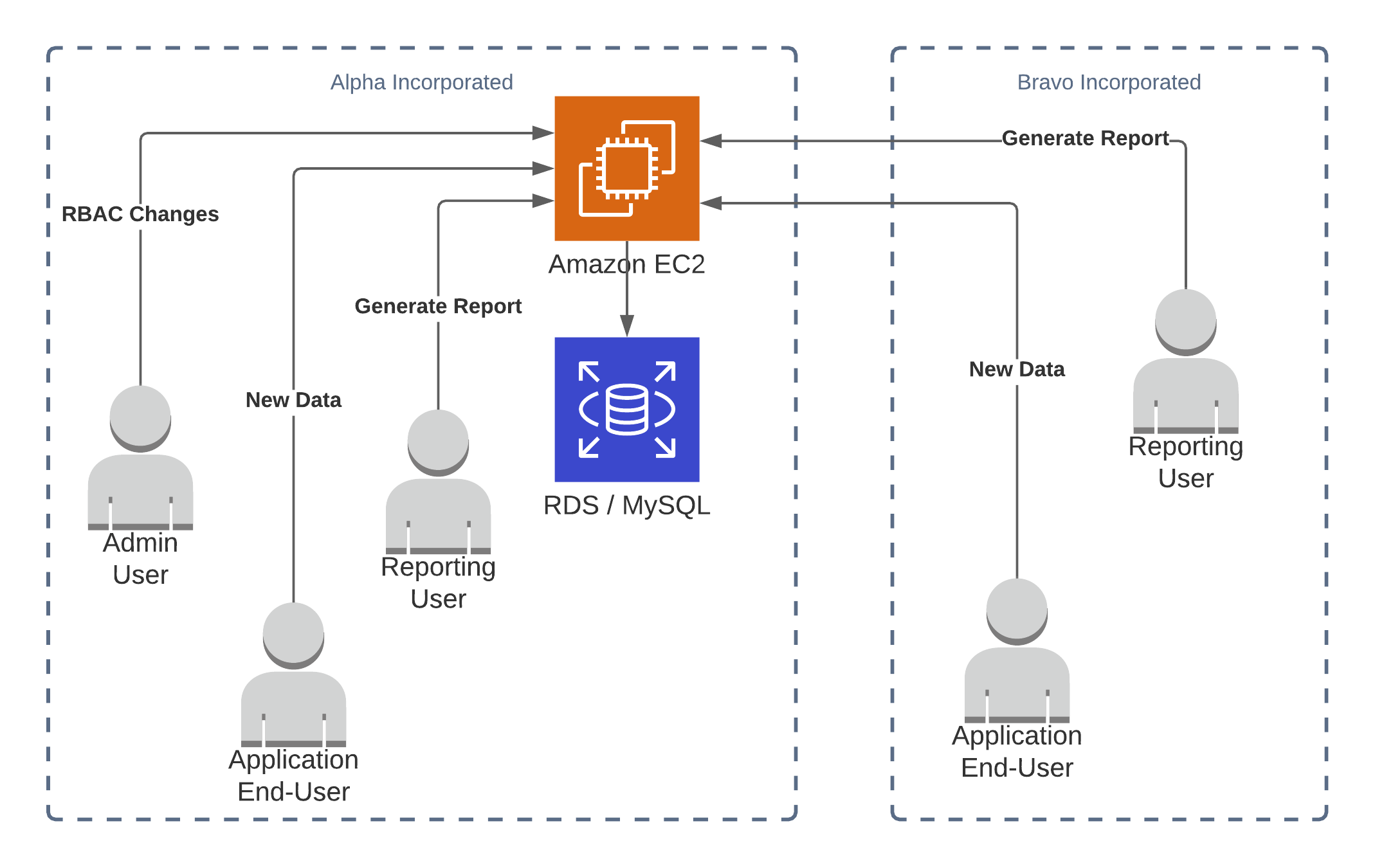

Version 1 of the real-time data sharing product

In our first version of the system, the tools we have available to us are a SQL database, a web framework, and instances to run them on. We don’t have managed services like Lambda, S3, or Step Functions. To make sure we have verifiable histories, we need to be able to provide audit logs and point-in-time reports in case of disputes. In most SQL databases, once an UPDATE has been performed, the record is modified and there’s no simple way to undo the change.

Event logs and versioned records both give us ways to travel back in time. Take the versioned approach for example:

uuid | version | version_ts | data

1234 | 0000001 | 2020-02-20 | the first transaction

1234 | 0000002 | 2020-03-30 | the settlement transaction on the same order

1234 | 0000003 | 2020-04-04 | the third event regarding the same order

This approach gives us something like double-entry bookkeeping, but it allows us to query by time as well as view the whole history of a single order/item when trying to settle disputes. To grab an order’s state on a particular date we can query WHERE uuid = 1234 AND version_ts < 2020-04-01 and will see all but version 0000003. For multiple transactions, or to build a report from a specific date, we can drop the uuid = specification and use that world state to build a report. But notice that the same application that’s writing data to the SQL database is responsible for both assigning version IDs and timestamps. This means we have application logic responsible for both the actual calculations of state and the verification of that state.

The reports help give us confidence that we can view prior state and review transactions in the event of a dispute, but because the business logic and the trust system (versioning/timestamping) live in the same codebase there are limits on what we can validate. Bugs could be introduced to both business logic and the audit logging at the same time, changing the guarantees on what can or cannot be updated.

Version 2 of the real-time data sharing product

The V1 of our system was mostly successful – we got approved to continue development and make better promises to our users about the trustworthiness of our solution. Unfortunately, there are some shortcomings in V1 that are going to be difficult to address.

Our design is centralized to a single SQL database under a single party’s control, the owner of the SQL DB. A single SQL database means we have a single system that can be compromised and have records tampered with. A SQL statement like UPDATE data='evil lies' WHERE uuid=1234 AND version=0000002 would be enough to invalidate our historical record of prior versions. It also wouldn’t be detectable in the reporting system if we build the reports on-demand.

There are two basic approaches to prevent tampering with history. We could generate reports on a schedule and cryptographically sign them, or use a hash-based attestation system where transaction senders could validate that the transaction they are reading is the same as the one they wrote originally.

In V2 we want to be better about providing a history that we can verify isn’t changed. To do that, let’s take a page out of git‘s playbook and use Merkle tree style hashes:

uuid | parent_hash | version | version_ts | data

1234 | 0000 | 0000001 | 2020-02-20 | the first transaction

1234 | ae6b | 0000002 | 2020-03-30 | the settlement transaction on the same order

1234 | 89fc | 0000003 | 2020-04-04 | the third event regarding the same order

This new parent_hash property lets us store the hash of the data our parent contained, and we generate it with several inputs from our parent to make sure that the time, data, and parent-of-our-parent cannot be changed. In code, this would look something like sha256(parent.parent_hash + parent.version_ts + parent.data). If any of the important properties on our parent change, we can easily generate a hash ourselves and see that the hash is correct. Now an attacker would have to tamper with a whole lineage of a transaction from 0000002 onward and rebuild the hashes.

This process allows us to use a “latest” transaction to verify the entire history up to that point, and make sure that the world state we believe to exist is built with a the “blessed” lineage of transactions.

However, storing the data in the same database as the hashes we still have significant risk of tampering as anyone else could calculate new hashes after modifying whatever they like. To thwart that, we need to add a layer of secret-key signing by the different parties. When someone submits a new transaction they need to hash it on their side and sign that hash, similar to how JWT has both a hash and a signature included in all requests. Adding a signature means that an attacker would need to not only recalculate all the hashes, but also have access to the private signing keys of all parties involved in that transaction. With these signatures included, we can verify the hashes and also validate the signatures against public keys for each party. In this example, rb, gd, and tw are all separate parties adding records to our transaction.

uuid | parent_hash | sign | version | version_ts | data

1234 | 0000 | sig_rb | 0000001 | 2020-02-20 | the first transaction

1234 | ae6b | sig_gd | 0000002 | 2020-03-30 | the settlement transaction on the same order

1234 | 89fc | sig_tw | 0000003 | 2020-04-04 | the third event regarding the same order

Finally! We have a system where people can submit transactions and trust that the person controlling the SQL database can’t tamper with the underlying records. We can use the REST API provided to send new transactions or to read the current state of the database, and if we want to validate changes we can see the history and know that the signature process prevents changes from being made retroactively.

There is still an issue though: if a transaction is completely removed and it was the latest in the list, we have no way to know that it was deleted. This violates our expectations of non-repudiation. For example, if someone offered to purchase something and then later deleted it we wouldn’t be able to prove conclusively that they had removed the offer. Worse, if the owner of the SQL database deleted certain histories entirely we wouldn’t have a way to tell.

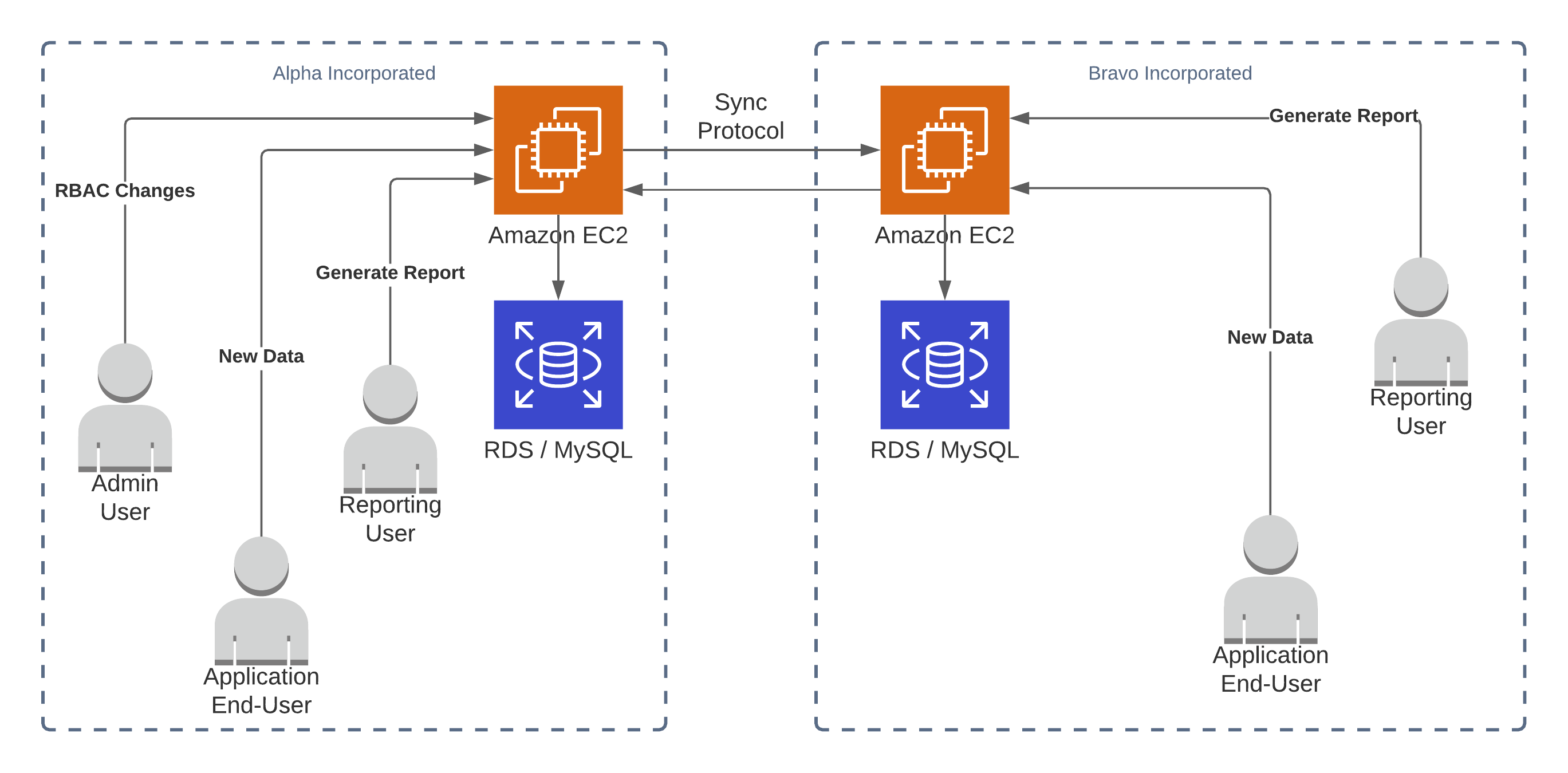

Version 3 of the real-time data sharing product

Building up to V3, we’ve uncovered a few important properties for multi-party systems:

- Non-repudiation: Once a write is accepted, no party can claim that the write didn’t happen. This is different from reconciliation/correction in that an error in

tx_1can be un-done by a new writetx_2that rolls back the action taken intx_1. Bothtx_1andtx_2are included in the history and all parties can still see the unbroken history. - Height: The number of total accepted transactions, effectively

len(log). This helps enforce non-repudiation by making it impossible to roll back to some prior state of the world without a reconciliation process. - Transaction (or block): One entry in the overall log. A transaction may contain several writes, but maps to a single signature.

- Consensus: Agreement among distributed parties on a shared protocol or set of truths.

- Signing: Using a secret key to validate that an originator of one message is also the orginator of future messages signed by that key.

- Tamper resistance: The sum of all the guarantees of infrastructure security, historical correctness, height, signing, and non-repudiation that help enforce that any motivated party can’t change the data without consensus.

So here we are, with a need to solve the non-repudiation problem in V2. If clients request an up-to-the-minute report on a frequent basis that helps reduce the scope. A party could only really remove a transaction sent in since the last time someone other than them requested a report.

Instead of forcing anyone who cared about non-repudiation to pull reports constantly, what if we made a change to the architecture that split the trust issue from the business logic? This way, the business logic and the chain-of-trust are updated separately to avoid the chance of introducing bugs affecting both. This lets us have more trust that changes to the product don’t affect the integrity and non-repudiation guarantees of the trust system.

If we replicate all the transactions as they happen, we can be quite confident that a party couldn’t reach into our copy and remove an event that they had already sent. As with Outlook’s Message Recall Requests, trying to un-send a message already sent and replicated only makes people more curious to see what you are attempting to hide.

In V2 we already laid the groundwork for this by signing events with a private key like sign_function(event.parent_hash, event.uuid, event.version_ts, event.data). As long as an event is signed, we can validate that it was originally sent by the party that signed it, that its contents are the same, and that the event is in the correct place in the lineage of that transaction or item.

Signed messages also let us easily catch back up if we ever disconnect. To be extra certain, we can request catch-up materials from multiple parties to avoid any of them giving us bad summaries of what happened while we were disconnected. There’s still a problem: since each uuid has its own version chain, a user can sign their own transactions and add them on to the end if we are attempting to catch up.

To mitigate this, we need to have a monotonic counter or grouping for writes. The block system of grouping writes together and sign the batch lets us assign a counter to each block, the block’s height. If we know the expected height then we can make sure we are getting no more and no fewer transactions than there ought to be.

This means our data model is now composed of three basic data types. We have transactions (or writes, or deltas, etc), we have blocks (groups of transactions), and we have the materialized records (the accumulation of all the puts/updates/deletes representing the current state of all the historical data). We can rebuild the materialized records for any point in time by replaying the blocks in order up to that point, giving us confidence in the existing materialized records and an easy way to check the integrity of those records.

What type of real-time, multi-party tool do you need?

In this journey, we’ve covered a bunch of pitfalls when multiple parties need to agree on some lineage or history. A ledger on its own is sufficient for some cases, but the multi-party aspect requires a distributed ledger to give us tamper resistance and non-repudiation we want in our system.

- In V1 we were missing signing, non-repudiation, and consensus.

- V2 added basic signing but still lacked distributed components.

- Finally in V3 we were able to build in signing, non-repudiation, and consensus.

Distributed ledgers provide these properties and more, and require some distinction from what’s colloquially referred to as “blockchain technology.” Because of it’s buzzword-y status, blockchain has become a fairly confused term that can be any mix of proof-of-work, proof-of-stake, and proof-of-authority distributed ledgers or basic lineage/cryptographic PKI infrastructure.

Try Vendia Share

Explore our business blockchain solution and download the app to see what its potential and start building. You can also request a demo or a five-day proof of concept to see how the platform can make an impact for your organization.